Ann Chamberlain and Christine O’Brien Beydoun

From the beginning of the Great War in August, 1914, neighborhoods across America such as Forest Hills demonstrated their support of the Allies by engaging in a variety of fundraising and war relief efforts. When the United States itself entered the war in April, 1917, these efforts intensified, including campaigns to support U. S. troops abroad, endeavors to boost morale at home, and campaigns to help fund the U. S. war expenditures by buying war bonds. The Forest Hills Gardens Bulletins from these years vigorously reported and encouraged these activities and provide vivid examples of the patriotism and generosity of the local residents.

Community War Relief Activities. When the Great War started in 1914, Forest Hills Gardens was just four and a half years old. There were only 500 or so houses (there are about 900 today); none of the large apartment buildings had been constructed. And yet, the magnitude and scope of war support activities were remarkable.

From early in 1915, the FHG Bulletins report weekly meetings of the War Relief Committee of Women’s Club of Forest Hills (itself founded in 1913), to which all “women of the Community” were welcome. This group grew in number and worked actively with the Girl and Boy Scouts before the United States’ entry into the war, then throughout the duration of the war itself, finally welcoming the returning troops back home with dinner parties, dances, and patriotic signs and gatherings at the Forest Hills railroad station. Nearly 500,000 returning troops passed through Forest Hills on their way from transport ships in New York Harbor to army camps on Long Island to be demobilized.

Local Girl Scouts worked with the War Relief Committee to make pillows for use in hospitals and ambulances overseas. They successfully undertook a community-wide campaign to produce 5,000 10” x 14” pillows, counting on each Forest Hills Gardens household to provide 10 of these pillows. The Girl Scouts worked with the Boy Scouts to construct surgical compression bandages from oakum (a strong fibrous material somewhat like tree bark) and covered in heavy muslin. It was the Boy Scouts’ job to cut the oakum, and the Girls Scouts’ to sew the covers. At the beginning of 1917, the weekly output of these oakum pads was between 250 and 350, with an effort to increase that number to at least 500.

Neighborhood Boy Scouts also put on a special “Army Hut” fund-raising event that included a staging of troops behind the front lines heading for the trenches. The $.25 admission fee was collected to “adopt” four “fatherless” French children for a year ($36 per child per year). More than a million Frenchmen were killed, missing in action or otherwise unaccounted for by the end of the Great War. And, of course, the Boy Scouts helped sell Liberty Bonds throughout the war.

War Bonds. Liberty Bonds were war bonds sold in the United States to support the Allied cause and U. S. efforts in the Great War. Offered at face value (that is, a $100 bond sold for $100), the bonds paid interest at between 4% and 5% and matured in four years. Becoming a symbol of patriotic duty at the time, the bonds were actively marketed to the “common man,” as well as to banks and other institutions more typically involved in investments of this kind, often through popular “bond rallies” sponsored by the government.

The funds raised by the Liberty Bonds issued before the November, 1918 end of World War I were not sufficient. Consequently, an additional $4.5 billion of what were called “Liberty Victory Bonds” were issued in April, 1919. These were the bonds being promoted at the “finish the job” bond rally held at the Forest Hills Inn on May 5, 1919. You will be heartened to learn that Forest Hills residents and organizations contributed so much that the quota of $106,000 was nearly trebled, the Forest Hills Women’s Club “rendered patriotic songs throughout the evening in a highly acceptable manner,” and “boys of Forest Hills who have come home from the war” were on hand to give talks and “receive a hardy greeting.”

Teddy Roosevelt in Station Square, July 4, 1917. Rejecting more than 500 other invitations to speak on the July 4th following the United States’ entry into the war, Theodore Roosevelt, the 26th President of the United States (1901-1909), came to Forest Hills Gardens and gave his famed “100% American” speech to a crowd of more than 2,000 from the steps of the red, white, and blue festooned Forest Hills railroad station overlooking Station Square. Perhaps Teddy chose Forest Hills on account of the community’s tradition, even in its infancy, of spectacularly festive and elaborate 4th of July celebrations. Annually, Gardens residents dressed up as revolutionary dignitaries and gathered around a very patriotically decorated Station Square, children were entertained with games and puppet shows, and a specially printed “Declaration,” announcing and commemorating the day of our national founding, was produced and distributed throughout the neighborhood. The 1917 Declaration specifically mentioned in its last line the fact that the nation was at war so “that the world may be made safe for democracy.”

Teddy vehemently insisted in his speech that, notwithstanding that we are a nation of immigrants, “our allegiance must be purely to the United States. We must unsparingly condemn any man who holds any other allegiance.” His concern, it was understood, was that German-Americans, or even French- or British-Americans, would have a detrimental effect on the U. S., particularly in times of war, if their allegiance were not exclusively to the United States.

You might be surprised by how patriotic Americans were in 1917, and indeed, how very fearful of anarchists, spies, sedition and treason they were at that time. At the height of World War I, the June 29, 1918 issue of the FHG Bulletin contained an announcement, startling to us, of the formation of a Forest Hills Vigilance Committee organized to “prosecute cases of disloyalty occurring in Forest Hills and vicinity.” Residents were invited to report, anonymously or not, but in any event on a confidential basis, any such disloyalty among their neighbors.

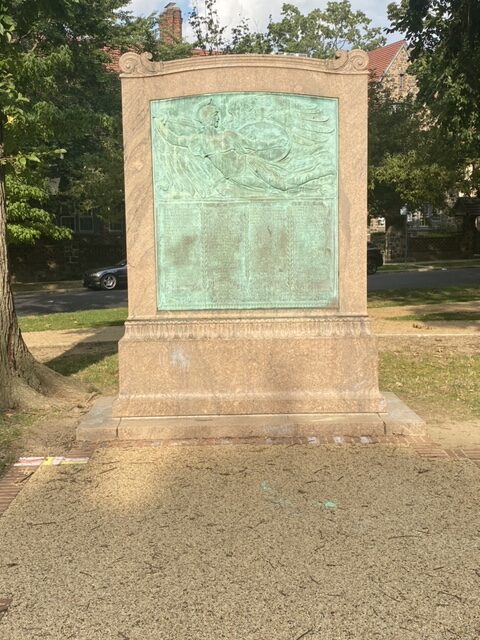

Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument in Flag Pole Green. You should take the time to visit the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument on the north side of the flagpole in Flag Pole Green. Designed in 1919 by Alfred Weinman, one of the most respected American sculptors of the period, who lived at 234 Greenway South, the monument was paid for by contributions from Forest Hills residents, and dedicated on October 10, 1920.

This granite and bronze monument features a relief sculpture of a winged female figure symbolizing “The Call to Service Overseas” and lists below the relief the names of the Forest Hills men who answered that call. You will note how different this monument is from the typical war memorials featuring a cast iron soldier holding his weapon atop a plaque or edifice with the names of those of the community who gave their lives for their country that occupy the centers of villages and towns across the nation. For this Forest Hills monument was not intended to be a war memorial at all: it was not an evocation of war but, rather, a call to service; it was not dedicated to or did it list the names of those who lost their lives, but rather commended those who served.